I’ve been a psoriasis-affected person for many more years than I’ve been an anthropologist and filmmaker. I mention this because it is a crucial fact in making BROKEN SKIN. My own experience of struggling, giving up, questioning and finally healing are important factors in approaching this disease through a film.

In September 2016, I started my master course in Visual Anthropology at Goldsmiths University of London. I realised that psoriasis and my ongoing healing process would be an interesting topic for my graduation film. Although I still feared the comeback of the disease I wanted to take the chance to work in an auto-ethnographic way, meaning involving personal experience. Like this I could take a look at it through an anthropological lens. I prepared my list of questions like ‘How can the representation of psoriasis be challenged?’ ‘How do people relate to those images and the stories around psoriasis?’ ‘How are people experiencing it in their daily life?’

Psoriasis causes scaly and flaky symptoms on the skin, such as patches that can grow. They can be itchy and sore, and through scratching and picking, they will crack up and bleed. It is a disabling disease with no clear cause or cure and as a result psoriasis-affected people can suffer psychologically to an immense extent and it is therefore considered as a “lifetime experience”. Incurability is a crucial factor in experiencing this disease.

I conducted my research from August 2017 to May 2018 in the UK and Switzerland (where I am from). It involved psoriasis-affected people between the age of 21 and 67, living with it from one to 40 years. The participants were from varied ethnic backgrounds and identified themselves as either male or female. Some of the participants responded to an announcement that I sent via email to King’s Hospital London and Royal Hospital London, put on social media and placed around Goldsmiths University campus or was made at the Psoriasis Association meeting in 2017 and 2018. In addition, the intention of the research was circulating it among friends.

The focus of the beginning of my work laid very much on the audio. The first round of conversations involved 20 individuals in the UK and Switzerland which resulted in 20 hours of recorded audio material mainly exchanging experiences about psoriasis and everyday life. The focus in the second round of interviews was on 12 of those individuals who gave consent that their recorded voices could be used in my film. It resulted in 6.5 hours of audio material from which the quotes are retrieved. Open-ended questions were asked rather than closed ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions to elicit open reflection and responses. The primary purpose of these questions was to produce engaging material for the film. To say that I struggle with the same condition helped a lot in gaining trust and getting deeper.

I delved into the accounts of my participants and got completely lost. I was listening, editing, shortening, re-listening and transcribing which lead to 80 pages consisting of 40’000 words. Slowly I started thinking about images. It was difficult find the patience doing this and not to think about the images too early. But it was worth it. Then I explored different materials and surfaces using a macro lens. Since I had all the quotes in my mind I knew exactly which image would resonate with a quote in a sensorial or visual way. BROKEN SKIN explores the visual representation of the stories told and how this shapes peoples’ outlook on healing. My goal was to find images that would not spread fear but could explore psoriasis on these different, also organic, surfaces also to allow beauty in that context.

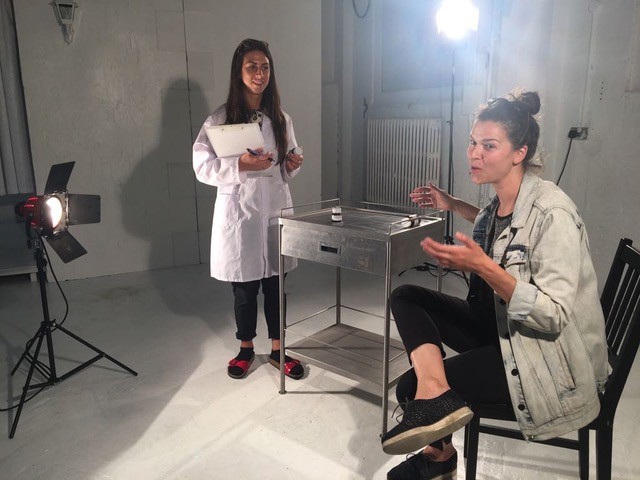

I wanted to include my personal story from the beginning of the project. To work in an auto-ethnographic was is a huge privilege because you can reclaim the narrative of your experience. This is the reason I decided to reenact a doctor scene (where I play myself going to the experts but they are not able to help me). Through the use of music and the exaggerated acting I could liberate myself from that negative experience. The other sequences were filmed along the way. Like the water scene (where I fall into the pool with my clothes on) that we filmed with a GoPro. It was a lot of playing around, trying things out, evaluating, shooting again. The only limit we had was time. We had maximum one day for the shoot for each sequence. I trust this playful process very much and it was possible with the right people.

During the process I switched a lot between the positions of a psoriasis-affected person and an anthropologist. Of course you could say that these boundaries are blurry anyway, but it actually helped me in approaching the making of the film. It has something to do with the distance towards the topic and the people I met.

While I started to experience my own story in a different light (I was writing diary a lot) I entangled it with other people’s stories. There was a parallel exploration of psoriasis and this gives the film its simple narrative structure. From the beginning of the project I didn’t want to show the people behind the voices. The reason for that was to emphasise their accounts and visually represent them in an uncommon way. However, at the end of the process I changed my mind. It felt right for me and it gives the film a more human touch which was important for exploring psoriasis.

Before going public with the film I showed it to the interviewees and I was extremely nervous. They gave me a lot of time, personal insights and we talked about fears and hopes and really deep meanings. So it was very important to me that they were happy too. I got approval from all of them and it generated for almost everyone a new perspective on the disease.

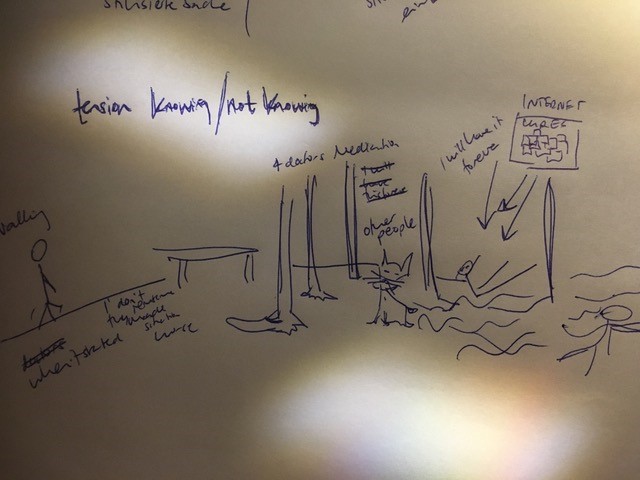

The biggest challenge for me was to switch between the psoriasis-affected person who shared similar frustrations and other feelings and the anthropologist who is trying to explore the topic in a more distant way. It felt like juggling two extremes around me all the time. Another challenge was the narrative structure. Which are the moments where these different stories meet? I could solve this problem by hanging the quotes on the wall, listening to cut out moments and trying out new combinations.

Through my ethnographical practice I learnt to open up in order to listen and relate to other stories and examine them through an anthropological lens. The most important part for me is: I no longer fear this disease. My perspective has changed and it isn’t paved by frustration anymore, but by knowledge. This is something that anthropology and filmmaking can do.